Manhattan Project – A History Lesson in a Rock Song

- Mark Stansell

- May 10, 2021

- 13 min read

Updated: Dec 2, 2021

Rush’s song from the 1985 LP, Power Windows, packs an incredible amount of history and imagery about the development and deployment of the first atomic bomb into just under 200 words and five minutes of progessive rock.

Imagine a Time, When it All Began

In November 1905, Einstein published his fourth paper that year, “Does the Inertia of a Body Depend Upon Its Energy Content?,” which contained the first iteration of the now famous equation, E=mc^2. This paper, and the ideas embedded in the equation, that mass and energy are essentially interchangeable, eventually led to the development of nuclear power, or as the nomenclature was then – atomic power. It took almost 27 years until physicists, on April 14, 1932, were able to implement some of the practical aspects of this with the first splitting of an atom, lithium, at the University of Cambridge.

Ten months after that historic event, on January 30, 1933, Hitler was named as Chancellor of Germany.

Just over five years later, in late 1938, the German chemists and physicists Otto Hahn, Lise Meitner, and Fritz Strassmann recognized that uranium would split when bombarded by neutrons.

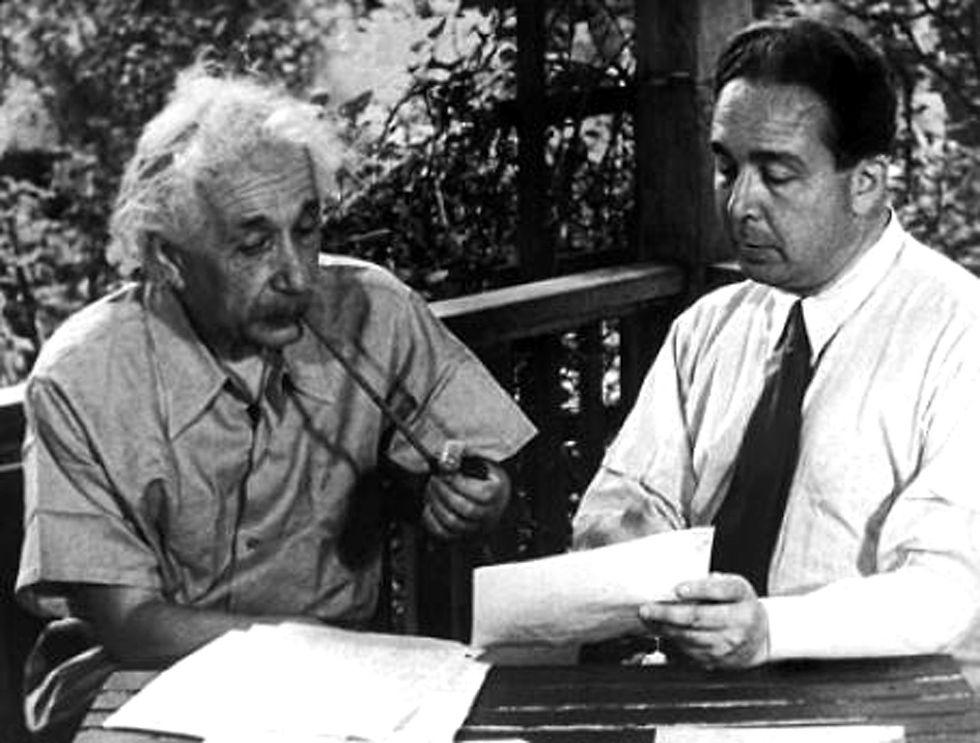

Later in the year, on August 2, Einstein, at the urging of several Hungarian-American physicists, most notable Leo Szilard, sent a letter to President Truman. In his letter, he discussed the use of uranium in the construction of bombs and recommended that the administration set up an office to laisse between the government and physicists working throughout the U.S. on atomic chain reactions.

Seven weeks after, on October 21, the Advisory Committee on Uranium met for the first time in Washington DC, which was the genesis of what would become known as the Manhattan Project.

A Scientist Pacing the Floor, in Each Nation

During the war, the Allied Powers were the United Sates, United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union. Among other Allied States were China and India. The Axis Powers were Germany, Italy, and Japan. Interestingly, Finland and Thailand were on the side of the Axis Powers. In his lyrics, Neil Peart makes the oft forgotten point that the U.S. was not the only country working on an atomic bomb.[1] The British, Soviets, Germans and Japanese all had programs in various stages of development with the sole aim of producing “the best big stick.”

All of the Brightest Boys

Even a partial listing of scientists involved with the Manhattan Project, as well as the German program, reads like a star studded “who’s who” registry from the golden days of physics. The academic connections across the Atlantic, especially between the American, British, and German programs might surprise many today.

While Einstein, who was born in Germany, and emigrated to the U.S. in 1933, did not work directly on the project, his letter was certainly a catalyst in getting the project initiated, and his equations were instrumental in its success. During the years of the Manhattan Project, he was teaching at Princeton.

J. Robert Oppenheimer was in charge of the facility at Los Alamos and is basically “the father of the atomic bomb.” He started his graduate work at Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, England under J. J. Thomson, who discovered the electron. Oppenheimer completed his graduate studies under Max Born at the Institute of Theoretical Physics at the University of Göttingen, Germany.

Enrico Fermi, the “architect of the nuclear age,” originally from Rome, created the first nuclear reactor and in 1944, Oppenheimer brought him to Los Alamos. Fermi also studied under Max Born at Göttingen. It is likely that Fermi was actually the first to split uranium during his 1934 experiments, however, he failed to recognized the process.[2]

Niels Bohr, a Danish physicist, worked as a consultant to the Manhattan Project. Bohr’s standard model of the hydrogen atom, which the first to offer practical explanation for atomic spectral lines and a key step in the development of quantum mechanics, earned him the 1922 Nobel Prize in Physics.[2] He founded the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen.

Richard Feynman, perhaps best known by undergraduate students for Feynman Diagrams, used to describe nuclear reactions, but also one of the most influential of American physicists, was a graduate student at Princeton when Oppenheimer recruited the Princeton team to come to Los Alamos. He later went on to make significant advances in quantum mechanics and quantum electrodynamics. However, while at Los Alamos, he was friends with another German physicist, Klaus Fuchs, who later confessed to spying for the Soviets. This and several other questionable relationships, later caused Feynman some difficulties with the FBI and his security clearance.

Hans Bethe, was another German born physicist and Nobel Prize winner, who emigrated to the U.S. in 1935, and was selected by Oppenheimer to work at Los Alamos. Bethe completed his doctorate at the University of Munich under Arnold Sommerfeld.

Otto Robert Frisch, another German born physicist, worked with both Lise Meitner and Niels Bohr. He became a British citizen in 1943 and the went to the U.S. to work at Los Alamos, where he was principally responsible for the theoretical designs of the triggering mechanism used in the atomic bomb.

Across the Atlantic, in Germany, Werner Heisenberg had also completed his doctoral matriculation under Max Born. Best known for the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, he was a key member of the German nuclear program.

The Pilot of Enola Gay

When he commanded the mission to Hiroshima, Paul W. Tibbets was already a seasoned aviator and a full colonel, all at the ripe old age of 30. Tibbets started flying with a barnstormer when he was just twelve, throwing boxes of Baby Ruth candy bars from the back seat to the crowds below. [3]

In December 1941, he led the first wave of ferry flights, which took B-17s of the 97th Bomb Group to England. Eight months later, as a major, he led the first operational mission of the B-17 Flying Fortress, which targeted a rail yard in northwestern France and was also the first test of high-altitude bombing. The mission marked the opening of the what would become the largest U.S. bombing campaign of the war.[3]

One month later, on September 6, 1942, Tibbets had his first true experience with aerial warfare. On a mission to bomb an aircraft factory in northern France, Maj. Tibbets watched as enemy fighters shot down another B-17 in the flight, which was piloted by his friend, Lt. Paul Lipsky. After pressing on to the target, Me-109 fighters attacked Tibbets’s plane. Shrapnel ripped apart his copilot’s hand, blood spraying all over the cockpit, and Col. Longfellow, the new 2nd Bombardment Wing commander, who was along for an orientation flight, lost his cool, grabbing the throttles over Paul’s shoulder. Trying to keep his copilot alive with one hand, he clobbered the frenzied colonel with his left elbow, knocking him out. Tibbets managed to get the aircraft back to England, and everyone survived, but he described the experience as[3],

… the most frightening brush with death that I was to experience in all my wartime missions over Germany, Africa, and the Pacific.

About eight weeks later, Tibbets was scheduled to fly General Eisenhower to Gibraltar in preparation for Operation Torch. Despite heavy fog and rain, which brought the ceiling and visibility to near zero/zero, Tippets successfully launched and delivered the general to his new headquarters.[3]

By January 1943, Tibbets had flown 43 missions and was transferred to staff duty, working for Colonel Lauris Norstad, who vetoed Tibbets’s field promotion to colonel, for as he said, there would only “be one colonel in operations.” However, a month later, the Chief of the Army Air Forces, Gen. Hap Arnold, asked Gen. Doolittle, who the 97th Bomb Group reported to after it was transferred to North Africa, to send his best bomber pilot to Boeing and assist with the plagued development of the B-29 Superfortress. Doolittle sent Tibbets and with his assistance, the plane was finally ready to deploy in early 1944. Technical issues aside, training had already begun for the troubled bomber and in March 1944, he was assigned as Operations Officer for the training unit, the 17th Bombardment Operational Training Wing (Very Heavy), based in Nebraska.[4][5]

Six months later, Tibbets took charge of the operational 509th Composite Group. The squadron had 15 B-29s and 1800 men. Tibbets chose Wendover, Utah as his initial base.[4] In January 1945, Tibbets was promoted to colonel and in May, he and the 509th deployed to Tinian Island, just north of Guam, where they continued training.[4] Only Tibbets and his Training Officer, Maj. Charles W. Sweeny had been briefed that the squadron was training to drop the ultimate weapon against Japan. Having no curiosity about the physics of the weapon, the commander of the 509th was more interested in the training his crews in the tactics to deliver the ten-thousand-pound bomb, which would have the same energy as 20 kilotons of TNT. Aircrews would have to make the drop from 31,000 feet then make a diving 155° turn after release.[5]

The Rising Sun, in the Dying Days of a War

In the middle of December 1944, the Japanese soldiers on the Philippine Island of Palawan committed what came to be known as the Palawan Massacre. 150 American POWs were locked in an air raid shelter, doused with gasoline, and set to fire. The Japanese shot or stabbed to death those who managed to escape. Amazingly, a few did manage to evade the gruesome carnage and lived to tell the tale.[5]

In April 1945, Roosevelt died, Trumann was sworn in as President, Mussolini was killed, and Hitler committed suicide (or so the official accounting goes). The Axis Powers in Europe surrender unconditionally to the Allied Powers on May 8.

Although the Allied forces were making headway in the Pacific theater against Japan, in the spring, news of the Palawan Massacre only added to the already heighted anti-Japanese feelings in the U.S. It is likely that news of the atrocity, combined with Trumann’s determination to end the Japanese imperial system, which was driving their racist war of conquest throughout Asia, along with the fact that the Germans had already surrendered, played into the decision of the Allied Commanders, who met at Potsdam, Germany on July 24 to issue the Potsdam Declaration, demanding the unconditional surrender of Japan.[5]

Peart would later write, when discussing the song[6]:

Modern revisionists seem to diminish the historical reality of that time – for example, the appalling brutality and racial genocide the Japanese had been inflicting in China, Korea, the Philippines and elsewhere. Mass killings of civilians (tens of thousands at a time, and totaling at least twice the Holocaust’s grim toll), biological and chemical warfare, inhuman treatment of prisoners of war, slavery, forced prostitution, medical experiments without anesthetic, vivisection, cannibalism – it’s a horrific list. To absorb that history, adding Japan’s alliance with the Axis Powers and the devastating sneak attack on Pearl Harbor that began the war in the Pacific, is to share an outrage that would have deserved any level of vengeance, to make it stop, and punish the perpetrators. Anyone who believes in the alternative – that the “humane” way to end World War II would have been an invasion of Japan – would only shift that death sentence to the American lives that such a suicide mission would have cost.

The Imperial Command ignored the Potsdam Declaration and continued to press the fight in the Pacific. Work had been progressing rapidly on the Manhattan Project, and leaders informed Truman that an atomic bomb would be ready on August 1. He issued the command[5],

…release when ready but no sooner than August 2.

At 3:00 pm on August 5, the mission was confirmed for the next day. Tibbets christens his B-29 the Enola Gay, after his mother. Late in the day ground crews load Little Boy, the bomb, onto the aircraft and the crew briefs for the mission. No mention is made of the type of weapon they are carrying. With clear weather, the Enola Gay launched at 2:45 am on August 6 for the six-and-a-half-hour flight to the target. Minutes later, the two chase planes, which would be recording the event, take off.

Fifteen minutes into the flight, the crew begins the arming process, which involves climbing into the bomb bay to insert the detonator and gunpower fuse. Three hours later, the two chase planes join up with the Enola Gay over Iwo Jima; the flight climbs to 9300 feet and heads to Japan. At 7:30 am, nearly four hours into the mission, the flight starts a climb to approximately 32,000 feet. At 9:05 am, the crews first spot the city of Hiroshima.

At 9:12 am (8:12 am Hiroshima time), the bombardier takes control of the aircraft and three minutes later, at 31,060 feet, he announces, “Bomb away.” Suddenly 9700 pounds lighter, the plane jumps as Tibbets takes control and executes the diving right hand 155° turn, which once completed had the aircraft 1700 feet lower and speeding away at full power.

In the morning rush hour of the city below, Little Boy explodes at approximately 9000 feet about 180 yards away from the aim point. In less than a second, the temperature on the surface is several million degrees hotter than the surface of the sun and within seconds the shockwave is expanding at supersonic speeds up to 984 mph. Instantaneously, the blast destroys 62,000 buildings, all utilities and transportation infrastructure and kills almost 80,000 humans.

By the time the bomb falls to the detonation altitude, Tibbets and crew are approximately eleven miles from the target. When the explosion happens, the crew feels the initial effects of the radiation blast in their bodies. Moments later, the first shock wave hits. No one was sure if the aircraft would survive; the airframe protests the assault, creaking, groaning, shuddering, but holds together. The second shock wave is lighter and the crew now knew they would survive. Tibbets announces over the intercom,

Fellows, you have just dropped the first atomic bomb in history.

The mushroom cloud rises to approximately 45,000 feet, some 15,000 above the altitude of the Enola Gay and the tail gunner can see it for nearly an hour and 45 minutes, when the plane is 368 miles away.

Twelve hours and thirteen minutes after launch, at 2:58 pm, Tibbets lands the Enola Gay safely back at Tinian Island.

The crew and other military celebrate at the officer’s club late that afternoon, but none of the scientists at Tinian attended. One of them remarked,

We knew a terrible thing had been unleashed.

The Song

Listen now to Manhattan Project, as Neil weaves so much history into so few words. For those unfamiliar, my suggestion is to use a quality headset, close your eyes, and let the band take you back to that time, now 75 years ago. Click on the album cover for a link to the studio recording.

Imagine a time

When it all began

In the dying days of a war

A weapon — that would settle the score

Whoever found it first

Would be sure to do their worst —

They always had before…

Imagine a man

Where it all began

A scientist pacing the floor

In each nation — always eager to explore

To build the best big stick

To turn the winning trick —

But this was something more…

The big bang — took and shook the world

Shot down the rising sun

The end was begun — it would hit everyone

When the chain reaction was done

The big shots — try to hold it back

Fools try to wish it away

The hopeful depend on a world without end

Whatever the hopeless may say

Imagine a place

Where it all began

They gathered from across the land

To work in the secrecy of the desert sand

All of the brightest boys

To play with the biggest toys —

More than they bargained for…

Imagine a man

When it all began

The pilot of “Enola Gay”

Flying out of the shockwave

On that August day

All the powers that be

And the course of history,

Would be changed for evermore…

Imagine a Man, Imagine a Time, Forty Years from Now

With all that is going on in the world today, one might ask why I chose to write about this song at this time.

The song is a powerful objective look at a pinnacle series of events in history. History, both accurate objective history, in terms of timelines, key players, events, numbers, etc., as well subjective history, in terms of the recollections, memories, accountings of those who actually lived it, not a reinterpretative spin decades or centuries later, is extremely important to humans both as individuals and as a society. The well-worn adage that those who do not know their history are bound to repeat it is an eternal truth.

Every song on Power Windows deals with some aspect of power, and Manhattan Project deals with what was then perhaps the ultimate power. During World War II, people knew and understood there was a war going on. What was unknown, until that August Day in 1945, was the work going on in secret to develop that power. The power that scientists unleashed was beyond the comprehension of most people, even today. Yet, it was necessary to prevent further death, destruction, and evil.

Today, we are in yet another war, but one of a very different, and far more insidious nature than those past. Unfortunately, most are woefully unaware of that fact. However, what many are painfully, or perhaps joyously aware of, is that scientists are working around the globe, in relative non-secrecy, on a power that may be far more dangerous, and sinister, than that developed and unleashed by the Manhattan Project.

Neil wrote the lyrics to the song in 1985, forty years after the fact, doing exhaustive research on the subject at a time when one actually had to read a book, or ten, to obtain even an overview, rather than just clicking on a few links returned by a search engine.[6] Notably, he was only 32 at the time, having been born in 1952, only seven years after the bombing of Hiroshima.

Imagine a man, born in 2027, writing and composing in 2060, at an age of 32 or 33. What will he write about the events of last year, about Operation Warp Speed, the people involved, and the power unleased in the last several months? Imagine, if you will...

Namaste folks and thanks for reading,

Mark

May 10, 2021

Postscript

The song has always been one of my favorites, for it touches on so many of my interests - physics, aviation, history, military history, and of course Rush. This article was a bit like a trip down memory lane for me, in so far as it took me back to my readings from my mid 20s and later at graduate school. On my book shelve, I have Easton Press copies, which I have read, of Einstein's The Meaning of Relativity and Feynman's Six Easy Pieces. In my master's thesis, I have calculations for the Fermi level in a certain material. Finally, at Naval Postgraduate School, I had the pleasure of taking two 400 level classes under Professor Karlheinz Edgar Woehler, who completed his doctoral thesis at the University of Munich in 1962 under Werner Heisenberg. Two degrees of separation, pretty cool!

References (not hyperlinked within)

[1] Body, Alex E. (2019). Rush, Song by Song, Fonthill Media Limited.

[2] Taylor, John R, & Zafiratos, Chris D. (1991). Modern Physics for Scientists and Engineers, Prentice Hall.

[3] Miller, Donald L. (2006). Masters of the Air, America’s Bomber Boys who Fought the Air War Against Nazi Germany, Simon & Schuster Paperbacks.

[5] Miller, Donald L. (2006). The Story of World War II, Simon & Schuster Paperbacks.

[6] Peart, Neal (2011). Far and Away, A Prize Every Time, ECW Press.

Bibliography

[C] Popoff, Martin (2020). Limelight, Rush in the ‘80s, ECW Press.

Live Performances

I intentionally chose the original studio recording of the song for the main body of the article, because for me, it is the strongest, with Geddy's vocals showing an almost ethereal quality.

The live performance from the 1989 DVD, Show of Hands Tour, has powerful videos. The performances were recorded April 21–24, 1988, at National Exhibition Centre, in Birmingham, United Kingdom

The live performance from the Clockwork Angels Tour Blu-ray has the added depth of the string ensemble, which accompanied the band on that tour. The performances are from shows in Phoenix, Dallas, and San Antonio (November 25, 28 and 30, 2012, respectively).

Correction May 23, 2021

I've corrected an error in the first section, which the way originally written indicated that Hitler was named chancellor in 1939, when, in fact, it was six years earlier in 1933.

_JPG.jpg)

I hope you are thinking along the lines of collecting these together for a book.